👨🔬 Biochemical Oxygen Demand kinetics, measurement, and analytical calculation

$\require{mhchem}$

This post consolidates notes from Princeton University course CEE308: Environmental Engineering Lab, taught by Professor Peter Jaffé in Spring, 2022.

BOD Kinetics

Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) kinetics can be well-described as a first order reaction:

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial t} = -kL\]Where $L$ is the concentration of BOD at time $t$ (units (mass $O_2$ demand)/(volume)) and $k$ is the first-order reaction rate (units time$^{-1}$). Solving this equation gives us

\[L = L_0e^{-kt}\]Since BOD is in units of mass $O_2$ per volume, the amount of oxygen utilized at any time t $y(t)$ is related to the initial BOD $L_0$ and the remaining BOD $L$:

\[y = \Delta L = L_0 - L_t\]Which, when substitued into the following equation, gives

\[y = L_0\left(1-e_{-kt}\right)\]Or in differential form

\[\frac{\partial y}{\partial t} = kL_0e^{-kt}\]Determining reaction rate and initial BOD conentration from observations

This final equation can be used to determine reaction rate $k$ and initial BOD concentration $L_0$ by linearizing the euqation using natural logarithm:

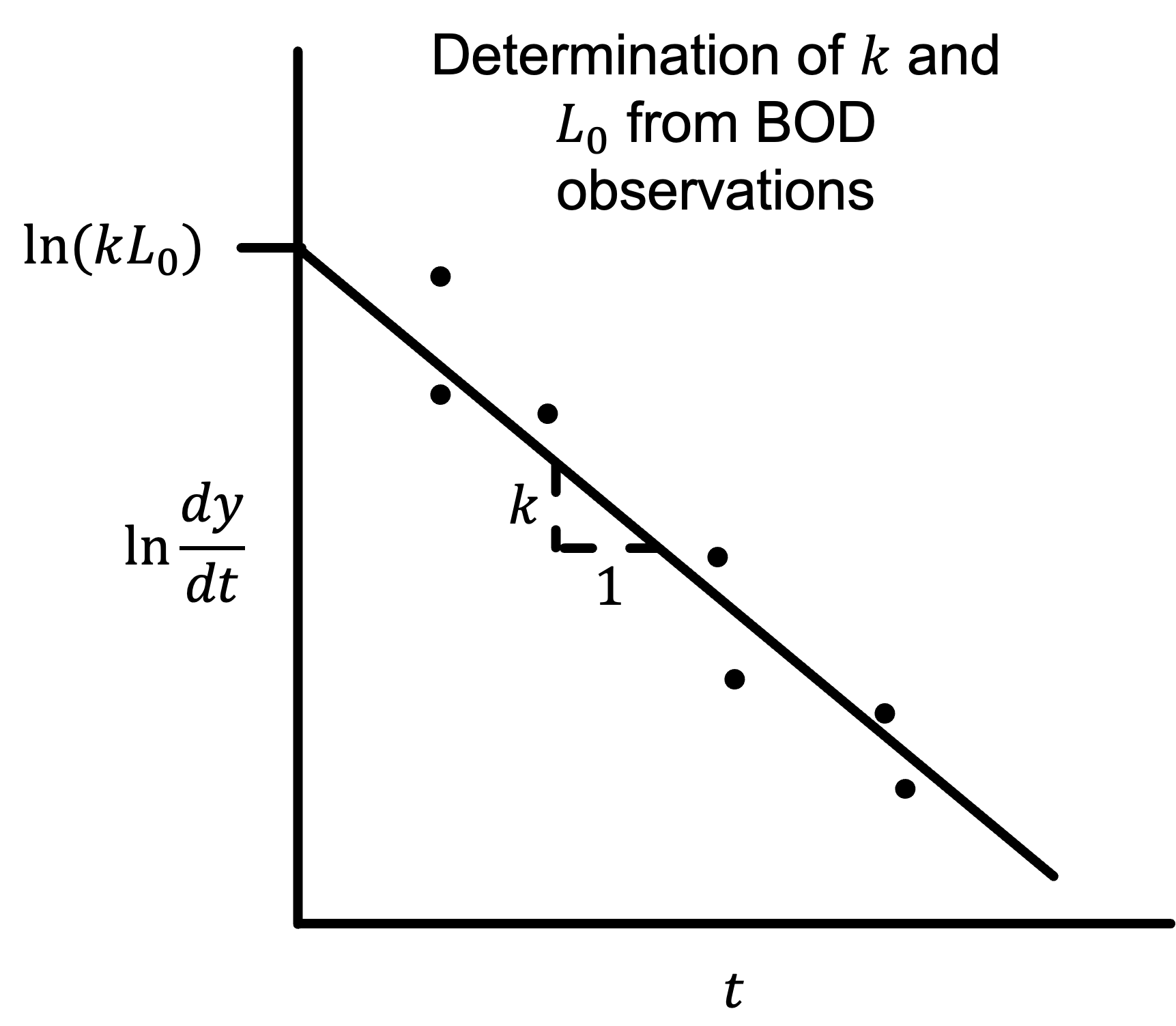

\[\ln\frac{\partial y}{\partial t} = \ln\left(kL_0\right)-kt\]This equation can be plotted to determine reaction rate $k$ and initial concentration $L_0$:

Where the slope is reaction rate $k$ and can be used along with the intercept $\ln\left(kL_0\right)$ to determine initial BOD $L_0$.

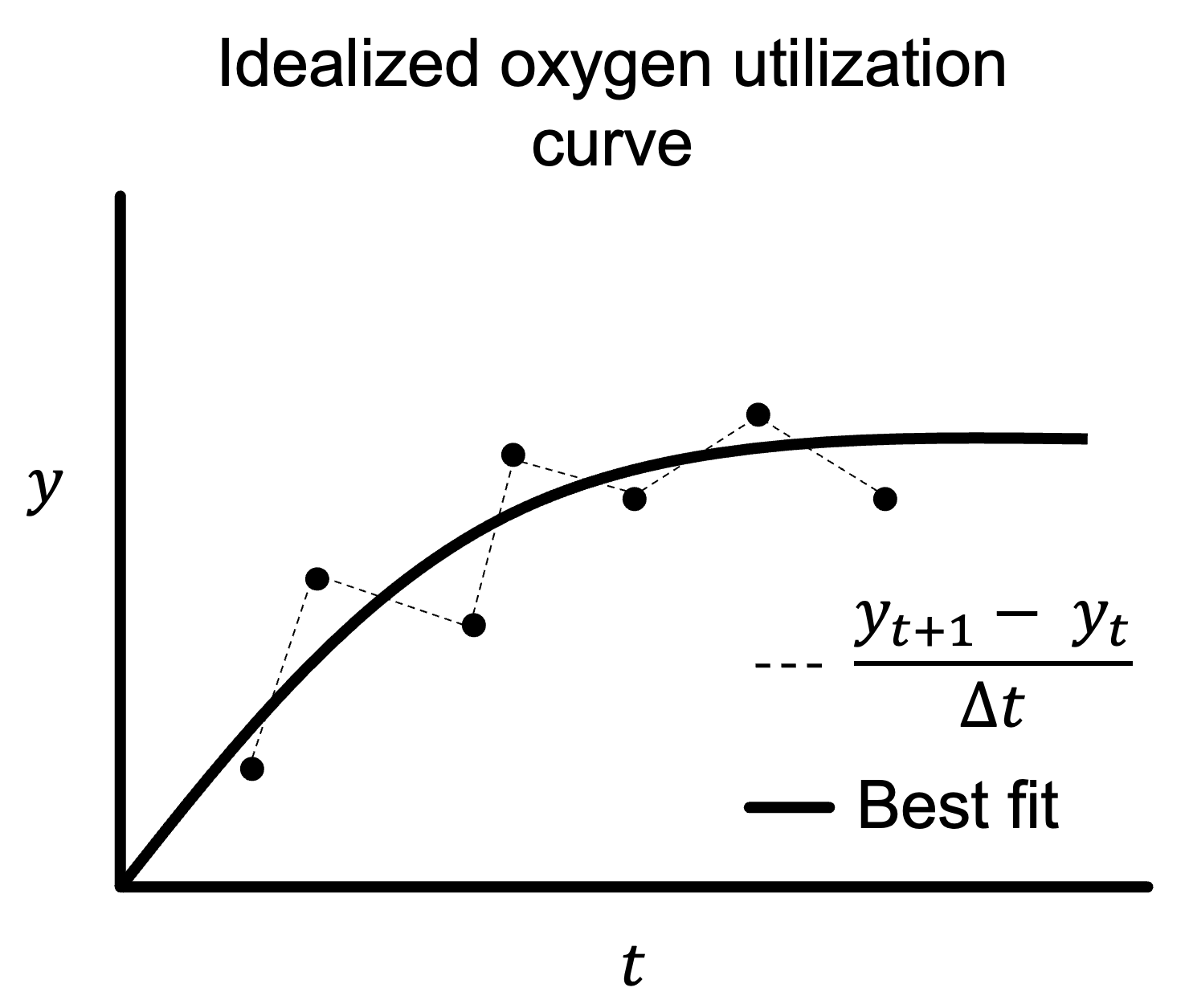

Computing $\frac{\partial y}{\partial t}$ is not straightforward. Consider the plot below titled “Idealized oxygen utilization curve.”

If you were to determine $\frac{\partial y}{\partial t}(t)$ as the change between two points (dashed lines), which means:

\[\frac{\partial y}{\partial t}(t) = \frac{y_{t+1} - y_{t}}{\Delta t}\]Then each $\frac{\partial y}{\partial t}(t)$ will have a wide variance, with some positive (the first dashed line between points in the above plot) and some negative (the second).

Best way to determine $\frac{\partial y}{\partial t}(t)$

However, we see that the generalized trend of $y$ over time in the “Idealized oxygen utilization curve” plot is increasing toward an asymptote. The best way to determine $\frac{\partial y}{\partial t}(t)$ therefore is to plot a best-fit curve and take the tangent of that curve at different points in time.

Determining theoretic BOD, c-BOD, and n-BOD

Theoretic BOD (or Total BOD) is the sum of carbonaceous BOD (cBOD) and nitrogenous BOD (nBOD) such that:

\[BOD_{tot} = cBOD + nBOD\]To determine $BOD_{tot}$ for a given input molecule, solve a stochiometric mass balance.

Example BOD calculation for Propanol

Suppose your input molecule is proponol, with chemical equation

\[\text{Propanol:}\;\ce{C3H7OH}\]Then write the mass balance

\[\ce{\mathbf{A}C3H7OH + \mathbf{B}O2 -> \mathbf{C}CO2 + \mathbf{D}H2O}\]And solve for stochiometric coefficients A,B,C, and D by balancing Carbon, then Oxygen, then Hydrogen. For propanol we arrive at the following stochiometric coefficients:

\[\ce{C3H7OH + {4.5} O2 -> 3CO2 + 4H2O}\]This stochiometric balance can be converted to BOD by computing the respective masses of required $\ce{O2}$ and propanol:

\[BOD_{tot,propanol} = \frac{4.5\;\text{mol}\times32\;\text{g/mol } \ce{O2}}{(3\times 12)+7+16+1\;\text{g/mol propanol}} = 2.4\;\text{g } \ce{O2}\text{/g propanol}\]Which, in this case, gives us mass $\ce{O2}$ requirements per unit mass propanol. Per-unit-volume BOD can be computed by multiplying by the concentration of propanol in the solution.

Determining cBOD and nBOD

The above example calculation for propanol gives theoretic total BOD as well as carbonaceous BOD. This is because total BOD = cBOD for an organic molecule with no Nitrogen. Oxidation requirements are purely carbon-related, or carbonaceous.

If, however, the molecule of interest has Nitrogen as well as Carbon, then total BOD can be split into cBOD and nBOD. To determine nBOD and cBOD from BOD, perform separate mass balances for the cases where Nitrogen in the molecule is not oxidized and where Nitrogen in the molecule is oxidized.

Suppose the molecule has composition

\[\ce{C_{$a$}H_{$b$}N_{$c$}O_{$d$}}\]To determine cBOD (carbonaceous BOD), solve the following mass balance where only Carbon is oxidized and where Nitrogen remains in reduced form:

\[\ce{\mathbf{A}C_{$a$}H_{$b$}N_{$c$}O_{$d$} + \mathbf{B}O_2 -> \mathbf{C}CO2 + \mathbf{D}H2O + \mathbf{E}NH3}\]Then, to determine total BOD (cBOD + nBOD), solve the following mass balance where both Carbon and Nitrogen are oxidized:

\[\ce{\mathbf{F}C_{$a$}H_{$b$}N_{$c$}O_{$d$} + \mathbf{G}O_2 -> \mathbf{H}CO2 + \mathbf{I}H2O + \mathbf{J}HNO3}\]Convert stochiometric coefficients ${A,B,F,G}$ to mass using molecular mass of each compound as done in propanol to determine total BOD (using F and G) and cBOD (using A and B). Then nBOD can be determined by subtracting cBOD from total BOD

\[nBOD = BOD_{tot} - cBOD\]Note on theoretical vs. observed BOD

Theoretical BOD (computed using stochiometric balances like those above) will always be higher than observed BOD. This is due to some electrons from Carbon and Nitrogen being used for microbial cel synthesis and maintainence instead of being completely oxidized for energy. Therefore, to adjust for cell synthesis and maintenance, engineers often multiply calculations of theoretic total BOD, cBOD, and nBOD by a factor of 0.92. This 0.92 factor assumes that approximately 8% of electrons from inputs are channeled into cell maintainance and synthesis instead of being transferred to atmospheric oxygen and therefore do not contribue to oxygen demand.

So, when you compute theoretical total BOD, cBOD, and nBOD, multiply your result by 0.92 to get a good sense of what you would observe in lab.